Red Rubber: The King Who Never Saw His Crime

How King Leopold II of Belgium orchestrated one of history's deadliest atrocities from his palace in Brussels, killing an estimated 10 million Congolese people in the pursuit of rubber wealth—a death toll comparable to the Holocaust. This is the story of a humanitarian facade that concealed industrial genocide, told through the voices of victims, missionaries who exposed the truth, and the monarch who never set foot in his empire of terror.

Act 1

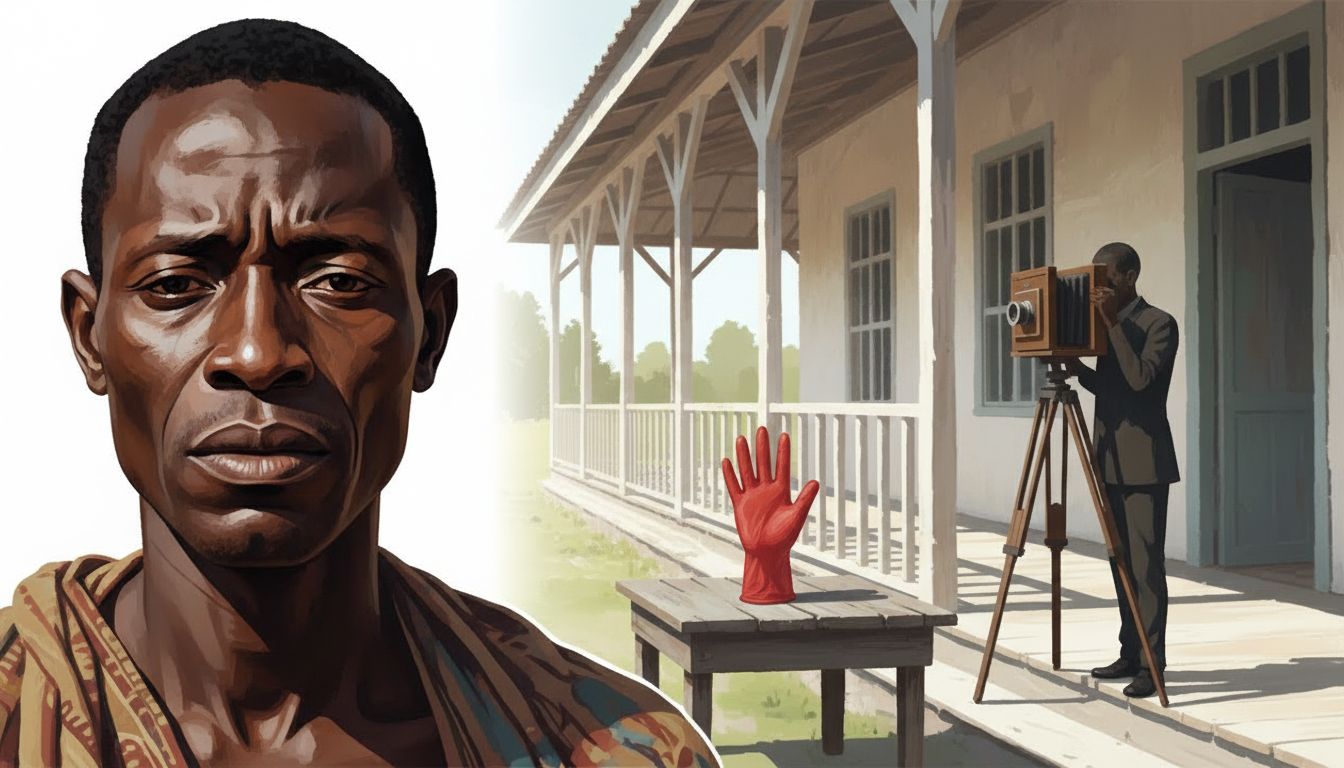

The Photograph

On May fourteenth, nineteen-oh-four, a man arrived at a mission station in the Congo carrying a parcel. Inside were the severed hand and foot of his five-year-old daughter. Her name was Boali. She’d been shot by a guard, dismembered, and eaten. His wife had been killed and cannibalized too. Eighty-three people died in his village that month because they hadn’t collected enough rubber. The missionary, Alice Harris, photographed the man—Nsala of Wala—staring at what remained of his child. That photograph would help bring down an empire.

Between eighteen eighty-five and nineteen-oh-eight, an estimated ten million people died in the Congo Free State. That’s a death toll comparable to the Holocaust. More than Pearl Harbor, more than the Titanic, more than Hiroshima. And it was overseen by one man who never visited the place once. King Leopold the Second of Belgium called his project a humanitarian mission to bring civilization to Africa. He promised to end slavery and throw back the shadows of barbarism. Instead, he created one of the most brutal forced labor systems in human history—a system built entirely on rubber extraction. This is the story of how bicycle tires and automobile demand killed millions.

Of the journalists and missionaries who exposed the truth using photography as a weapon. And of the man who ruled from Brussels, grew fantastically wealthy, and died in his palace having never seen the crime scene.

The Colonial Obsession

Leopold Louis Philippe Marie Victor was born in Brussels on April ninth, eighteen thirty-five. His father called him the little tyrant. His mother thought his hooked nose made him deformed. He was shy, awkward, walked with a limp. Nobody expected much from him. But Leopold had an obsession—one that began long before he became king. Colonies. In his twenties, he traveled extensively through the Dutch East Indies, Ceylon, Burma, India, China, Egypt.

Everywhere he went, he studied how empires extracted wealth from colonies. The Dutch system on Java particularly impressed him. Forced cultivation of crops contributed fifty-two percent of Dutch central tax revenues—four percent of the entire Dutch economy. In eighteen fifty-five, at age twenty, Leopold joined the Belgian Senate. Immediately, he began urging Belgium to acquire colonies. His colleagues ignored him. Belgium was small, prosperous, content. Why did they need an empire?

In eighteen sixty, Leopold gave his finance minister a gift—a paperweight inscribed with a message in French. It said: Belgium needs a colony. He wrote to government ministers exploring possibilities in Africa, Asia, South America. Everyone said no. He once told Kaiser Wilhelm the Second, while watching a military parade, that there was really nothing left for kings except money. On December tenth, eighteen sixty-five, his father died. A week later, Leopold the Second was crowned King of the Belgians. He was thirty years old.

And he finally had the power to get what he wanted.

The Humanitarian Mask

In the eighteen seventies, Central Africa was largely unmapped by Europeans. The Congo River basin—nine hundred thousand square miles of rainforest—was particularly mysterious. Then, between eighteen seventy-four and eighteen seventy-seven, an explorer named Henry Morton Stanley descended the Congo River, mapping its course. Leopold read Stanley’s accounts with intense interest. On September twelfth, eighteen seventy-six, Leopold hosted a conference at his palace in Brussels. He called it the International Geographic Conference. Scientists, explorers, and geographers from across Europe attended. Leopold’s opening speech was a masterpiece of humanitarian rhetoric.

He spoke of opening civilization to the last remaining region of the globe where it had yet to penetrate. Of throwing back the shadows still enveloping entire populations. Of a crusade worthy of this century of progress. Then he said something that, in hindsight, was almost insulting in its audacity. Must I reassure you, he asked, that when I called you all here to Brussels I was not motivated by selfishness? No, gentlemen. Belgium may be a small country but she is happy and contented with her condition. Everyone believed him.

Ferdinand de Lesseps—the man who built the Suez Canal—called Leopold’s plans the greatest humanitarian work of this time. Leopold founded the International African Association, publicly framed as scientific and humanitarian. Privately, he hired Henry Morton Stanley as his personal agent and sent him back to the Congo. Stanley’s orders were simple. Establish stations along the river. Secure treaties with local chiefs. Make sure the treaties ceded sovereignty to Leopold personally, not to Belgium. Between eighteen seventy-nine and eighteen eighty-four, Stanley obtained approximately four hundred fifty treaties.

Most of the chiefs who signed them were illiterate. Many didn’t understand what they were signing. Some treaties were later doctored by Leopold’s staff to include more favorable terms. But the world saw only the humanitarian facade. Leopold was bringing civilization to the Dark Continent. Ending slavery. Opening trade. Now he just needed international recognition.

The Berlin Conference

In November eighteen eighty-four, fourteen nations gathered in Berlin to carve up Africa. No African leaders were invited. The Sultan of Zanzibar requested permission to attend. His request was dismissed. The Berlin Conference lasted three months. European powers drew lines on maps, dividing territories they’d never seen among peoples they’d never consulted. Leopold’s representatives worked tirelessly behind the scenes. He’d already secured recognition from the United States—the first country to acknowledge his claim to the Congo.

On February twenty-sixth, eighteen eighty-five, the General Act of the Berlin Conference was signed. Leopold’s International Congo Society was officially recognized. The treaty required him to maintain free trade in the region and work to end the slave trade. He promised to do both. On June first, eighteen eighty-five, the Congo Free State was formally established. Leopold the Second became its sole owner and absolute autocrat. The territory was two point six million square kilometers—seventy-six times larger than Belgium itself. The population was estimated between ten and twenty million people.

And all of it—every acre, every river, every person—belonged to one man. A man who would never visit it once. For the first few years, Leopold ran the Congo at a loss. Ivory exports provided some revenue, but not enough. He borrowed money from the Belgian government. He sold bonds. He waited. And then, in eighteen eighty-seven, an Irish veterinarian named John Boyd Dunlop invented something that would change everything.

The inflatable rubber tire.

Act 2

The Rubber Boom

In the eighteen nineties, bicycles became a craze across Europe and America. Millions were sold. Every one needed rubber tires. Then came automobiles. Global demand for rubber exploded. In eighteen ninety-five, rubber sold for about three francs per kilogram. By nineteen hundred, it reached ten francs per kilogram. Prices had more than tripled.

The Congo had wild rubber vines growing throughout its rainforests. Leopold immediately pivoted from ivory to rubber extraction. In eighteen ninety-one and ninety-two, he issued decrees nationalizing approximately ninety-nine percent of the Congo and its resources. He created a concession company system. Private companies received territorial monopolies in exchange for giving Leopold a percentage of profits. The Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company—known as ABIR—was founded in August eighteen ninety-two with two hundred fifty thousand Belgian francs initial capital. In the early eighteen nineties, ABIR shares paid out about two francs per share in dividends. By nineteen hundred, the dividend was twenty-one hundred francs per share.

That’s a thousand-fold increase in less than a decade. The profits were staggering. But rubber doesn’t harvest itself. Congo rubber came from wild vines of the genus Landolphia—not cultivated trees like in Brazil. Congolese workers had to find the vines deep in the jungle, slash them, and collect the latex that bled out. The standard method involved slathering liquid latex on their arms, thighs, and chest, then waiting for it to harden. When they scraped it off, it took their hair and sometimes skin with it. An official in the Mongala basin estimated that rubber collection required twenty-four days of all-day labor per month just to meet quotas.

Twenty-four days. That left six days for everything else—farming, hunting, family, survival. In eighteen ninety-three, the systematic rubber collection system began in earnest. Rubber exports that year: five hundred eighty tons. By nineteen hundred: three thousand seven hundred forty tons. A five hundred forty percent increase in seven years. Leopold’s personal profit from rubber between eighteen ninety-six and nineteen-oh-five was estimated at seventy million Belgian francs. In today’s money, over one billion dollars.

But there was a problem. The Congolese people didn’t particularly want to spend twenty-four days a month in the jungle scraping latex off their bodies. So Leopold created a system to motivate them.

The Quota System

European agents were sent to establish posts in the concession territories. They surveyed villages and created censuses of adult men. The standard quota was approximately four kilograms of dried rubber per adult male every two weeks. Agents received a two percent commission on all rubber shipped. If production fell below quota, the agents’ pay was docked. This created a system where brutality was economically incentivized. Leopold also organized a private army called the Force Publique. By nineteen hundred, it numbered nineteen thousand soldiers.

By nineteen-oh-five, sixteen thousand African mercenaries commanded by about three hundred fifty European officers. Only white Europeans could be officers—Belgian regular soldiers plus mercenaries from other nations. The army consumed over fifty percent of the state budget. Force Publique soldiers were recruited—or more accurately, acquired—through several methods. Some were bought from chiefs. Some were kidnapped as children from villages and sent to Catholic missions for military training. All were required to serve a minimum of seven years. Their job was to enforce the rubber quotas.

If a village failed to meet its quota, punishments included imprisonment, flogging with a hippopotamus-hide whip called the chicotte, village burning, mass execution, and hostage-taking. Leopold never officially proclaimed hostage-taking as policy. Authorities in Brussels emphatically denied it existed. But the administration supplied each station with a manual that included instructions on how to take hostages to coerce local chiefs. Men, women, children, elders—entire families were imprisoned in stockades until their relatives brought rubber. In July nineteen-oh-two, one ABIR post recorded holding forty-four chiefs in prison simultaneously. At two stations in eighteen ninety-nine, death rates among hostages reached three to ten prisoners per day. Per day.

A British vice consul who visited in eighteen ninety-nine wrote that after the rubber was brought, the women were sold back to their owners for a couple of brass rods. Sold back. Like livestock. But the most notorious aspect of the Congo Free State wasn’t the quotas or the hostages. It was the hands.

The Severed Hands

European officers were concerned that Force Publique soldiers were wasting ammunition on hunting or keeping cartridges for potential mutiny. So they implemented a policy. For every bullet fired, soldiers had to produce proof it had been used to kill a person, not wasted. The proof was a severed human hand. Baskets of hands became the currency of the Congo Free State. Soldiers used them to make up for shortfalls in rubber quotas. To replace people demanded for forced labor gangs. To shorten their military service terms.

More hands meant shorter service. Some soldiers were paid bonuses based on the number of hands collected. A Swedish missionary named E. V. Sjöblom reported in eighteen ninety-seven that soldiers were rewarded with brass rods per basket of hands. One soldier told him the Commissioner had promised that if they delivered plenty of hands, he would shorten their service. This created a perverse incentive. Soldiers sometimes fired at animals for food, then cut hands from living people to make up their tally.

Survivors later testified they’d lived through massacres by acting dead—not moving even when their hands were severed—and waiting until the soldiers left before seeking help. Some units had a designated keeper of the hands. Hands were smoked over fires to preserve them for later presentation to officers. Historian Peter Forbath wrote that the baskets of severed hands, set down at the feet of European post commanders, became the symbol of the Congo Free State. On October tenth, eighteen ninety-six, Congo State soldiers attacked the village of Bandakea Wijiko because the rubber quality was deemed insufficient. Fifty killed, twenty-eight captured. All bodies had their right hands cut off. All of them.

In September eighteen ninety-nine, an American missionary named William Sheppard was sent to investigate a massacre in Bena Kamba country. Sheppard was the first Black American missionary to the Congo. The locals called him Mundele N’dom—the black white man. When he arrived at the massacre site, the tribal chief Malumba proudly showed him the evidence. Sheppard used his Kodak camera to document what he found. He counted eighty-one right hands cut off and being dried over fire before being taken to show State officers what had been achieved. He also found sixty women confined in a pen and evidence that bodies had been cannibalized. Mark Twain would later mention Sheppard by name in his satirical pamphlet King Leopold’s Soliloquy.

In it, Leopold complains about photography exposing his crimes. The kodak, Twain wrote in Leopold’s voice, has been a sore calamity to us. The most powerful enemy that has confronted us, indeed.

The Faces Behind the Numbers

Most historical atrocities reduce victims to statistics. Ten million dead. It’s a number so large it becomes abstract. But we know some names. Nsala of Wala—the man in Alice Harris’s photograph—staring at his daughter’s severed hand and foot. Boali, his five-year-old daughter, shot by a guard named Likilo, dismembered, cooked, and eaten. Bonginganoa, Nsala’s wife, shot by a guard named Mboyo, killed and cannibalized. Eighty-three people died in Wala in May nineteen-oh-four alone.

Eighty-three. Because of rubber. Mola Ekulite was a young man whose hands were destroyed by gangrene after Force Publique soldiers tied them too tightly and crushed them with rifle butts. Alice Harris photographed him too. Yoka was a child whose right hand was severed when his village failed to meet its rubber quota. He survived. His photograph also circulated internationally. Bolengo and Lingomo—two more victims from Wala whose severed hands were brought to the mission by Nsala’s brothers.

The Roger Casement Report contains testimony from dozens more. A witness identified only as U. U. described soldiers killing ten children in the water as people fled. They killed a lot of adults, he said, cut off their hands, put them in baskets, and took them to the white man, who counted two hundred hands. They killed my little sister, threw her in a house, and set it on fire. Another refugee told Casement about being forced deeper and deeper into the forest to find rubber vines. Their women had to give up cultivating fields and gardens.

Then they starved. Leopards killed some when they were working in the forest. Others got lost or died from exposure and starvation. We begged the white man to leave us alone, he said. We said we could get no more rubber. But the white men and their soldiers said: Go. You are only beasts yourselves. These are the voices that survived.

The ones who lived long enough to tell someone who wrote it down. For every name we have, there are thousands we don’t.

The Death Toll

How many people died in the Congo Free State between eighteen eighty-five and nineteen-oh-eight? We don’t know exactly. And that uncertainty is itself part of the crime. Leopold burned the entire Congo Free State archives before transferring power to Belgium. The operation took eight days. He told an aide: They have no right to know what I did there. The first census wasn’t conducted until nineteen twenty-four—sixteen years after Leopold’s rule ended. It counted ten to ten point three million people.

But we don’t know what the starting population was in eighteen eighty-five. Historians call the early estimates only wild guesses. Most scholars estimate the original population at between ten and twenty million. E. D. Morel, the journalist who exposed the atrocities, estimated ten million deaths based on a starting population of twenty million souls halved. Roger Casement estimated three million, but he himself called it almost certainly an underestimate. A Belgian commission in nineteen nineteen concluded that roughly half the population perished during Leopold’s rule.

Adam Hochschild, in his definitive book King Leopold’s Ghost, settled on approximately ten million—a death toll of Holocaust proportions. Where does that number come from? Not just direct violence, though there was plenty of that. In nineteen-oh-one alone, an estimated five hundred thousand people died of sleeping sickness. Swine influenza killed about five percent of the entire population. Smallpox ravaged communities periodically. But these diseases were exacerbated by the rubber system. When men spent twenty-four days a month in the jungle collecting latex, they couldn’t farm.

Families starved. Malnutrition made them vulnerable to disease. The years eighteen ninety-nine to nineteen hundred saw what contemporaries called a terrible famine. Entire villages fled into French Congo to escape. The birth rate plummeted because communities were too disrupted to sustain families. One historian estimated that in the Kuba region specifically, direct violence accounted for less than five percent of deaths. But that was just one region. The rubber provinces saw far worse.

Was it genocide? That’s debated. The United Nations definition requires intent to destroy a specific group. Leopold didn’t want to exterminate the Congolese—he wanted to exploit them. The deaths were, in his view, acceptable collateral damage. But Raphael Lemkin—the man who coined the term genocide—called it an unambiguous genocide. And Adam Hochschild, despite his careful scholarship, wrote that while it might not technically meet the legal definition, it was certainly of genocidal proportions. Ten million people.

More than died at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined. More than the Armenian genocide. Comparable to the Holocaust. And for years, almost nobody knew.

Act 3

George Washington Williams

The first person to expose Leopold’s crimes was an African American historian and pastor named George Washington Williams. Williams was born in Pennsylvania in October eighteen forty-nine to free Black parents. At age fourteen, he ran away to enlist in the Union Army under an assumed name and fought in the final battles of the Civil War. After the war, he attended seminary and became a Baptist pastor. In eighteen eighty, he became the first African American elected to the Ohio State Legislature. In eighteen eighty-two, he published History of the Negro Race in America from sixteen nineteen to eighteen eighty—considered the first comprehensive history of African Americans. W. E.

B. Du Bois called him the greatest historian of the race. In eighteen eighty-nine, Williams arranged to write articles for S. S. McClure’s Associated Literary Press. He secured an interview with King Leopold the Second. Leopold was very impressive in person—charming, eloquent, passionate about his humanitarian mission. Williams believed him.

In eighteen ninety, with support from President Benjamin Harrison’s administration, Williams traveled to the Congo to see Leopold’s civilization project firsthand. Leopold was alarmed when he heard about the trip. He urged Williams to wait. Williams went anyway. What he found was widespread brutal abuses and slavery imposed on the Congolese. On July eighteenth, eighteen ninety, from Stanley Falls, Williams wrote An Open Letter to His Serene Majesty Leopold the Second. It’s been called one of the greatest documents in human rights literature. Against the deceit, fraud, robberies, arson, murder, slave-raiding, and general policy of cruelty of your Majesty’s Government to the natives, Williams wrote, stands their record of unexampled patience, long-suffering and forgiving spirit, which put the boasted civilization and professed religion of your Majesty’s Government to the blush.

He wrote that Henry M. Stanley’s name produced a shudder among the Congolese people when mentioned. They remembered his broken promises, his copious profanity, his hot temper, his heavy blows, his severe and rigorous measures. And then Williams wrote something that would echo through the next century. All the crimes perpetrated in the Congo, he wrote, have been done in your name, and you must answer at the bar of Public Sentiment for the misgovernment of a people. He called them crimes against humanity. This was eighteen ninety. The term wouldn’t appear in international law until the Nuremberg trials—fifty-five years later.

George Washington Williams was the first person to use that phrase in its modern sense. Leopold and his supporters publicly denounced Williams’s charges. Privately, they spread rumors that Williams was a blackmailer or worse. A forty-five-page refutation was circulated in the Belgian Parliament. Even Williams’s patron suddenly withdrew support. Williams had contracted tuberculosis and pleurisy during his Congo travels. He moved to England in eighteen ninety-one to work on a book about colonialism in Africa. On August second, eighteen ninety-one, George Washington Williams died in Blackpool, England.

He was forty-one years old. His reputation was destroyed. His book was never finished. He fell into almost complete obscurity. And Leopold’s crimes continued for another seventeen years.

The Shipping Clerk’s Revelation

In nineteen hundred, a young shipping clerk in Liverpool noticed something strange. His name was Edmund Dene Morel. He worked for Elder Dempster, a company that handled cargo ships traveling between Belgium and the Congo. Morel spoke French, so he was frequently sent to Belgium where he could view internal accounts of the Congo Free State trade. And he noticed something that didn’t make sense. Ships leaving Belgium for the Congo carried guns, chains, ordnance, explosives, and ammunition. No commercial trade goods. No cloth, no tools, no manufactured items that could be sold or bartered.

But ships returning from the Congo were full of valuable rubber and ivory. The value ratio was roughly five to one. Morel understood what this meant. If no trade goods were going to the Congo to pay for these products, then the rubber and ivory weren’t being traded for. They were being extracted through forced labor. This wasn’t commerce. It was slavery. Morel discussed what he’d discovered with his employer.

He was met coldly and dismissively. The company offered him an overseas promotion. Then they offered him a lucrative consultancy in return for his silence. Morel refused both offers. In nineteen-oh-one, he left the company to become a full-time journalist. In nineteen-oh-three, he founded a journal called The West African Mail. He published his first pamphlet, titled The Congo Horrors. Then he published King Leopold’s Rule in Africa in nineteen-oh-four.

And Red Rubber in nineteen-oh-six. In Red Rubber, he wrote: King Leopold starts upon his Congo career by declaring that he has taken in hand a philanthropic enterprise. The whole of these vast sums are the proceeds of the rubber slave trade of the Congo, raised directly or indirectly from the unspeakable oppression, misery, and partial extermination of the native of Central Africa. Morel’s work began to reach people. But he needed more than economic analysis. He needed eyewitness testimony from someone the British government couldn’t ignore. He was about to get it.

The Casement Report

Roger Casement was born in Ireland in September eighteen sixty-four. He’d made his first voyage to the Congo in eighteen eighty-three at age nineteen, working for trading companies. Eventually, he joined the British consular service. In nineteen-oh-one, he was appointed British consul to the Congo Free State. On June fifth, nineteen-oh-three, Casement left his consular base on the Lower Congo River and traveled into the interior. He later said he ceased to be a consul and became a criminal investigator. For three months, he traveled through regions of the Upper Congo, interviewing missionaries, traders, and Congolese survivors. He documented everything.

On September fifteenth, he returned to Leopoldville and sent a telegram to the Foreign Office. I have returned from the Upper Congo today with convincing evidence of shocking misgovernment and wholesale oppression. In February nineteen-oh-four, the Casement Report was delivered before the British Houses of Parliament. Sixty pages with twenty pages of appendices containing individual testimony. It was well-structured, solidly factual, and detached in tone. Which made the content even more horrifying. Casement described villages depopulated by sixty to seventy percent since the rubber quotas began in eighteen ninety-three. He documented the hostage system in clinical detail.

When I asked if it was a woman’s work to collect rubber, he wrote, the official said, No; that, of course, it was man’s work. Then why do you catch the women and not the men? I asked. Don’t you see, was the answer. If I caught and kept the men, who would work the rubber? But if I catch their wives, the husbands are anxious to have them home again, and so the rubber is brought in quickly and quite up to the mark. The appendices contained testimony from Congolese witnesses. One, identified only as U.

U., described what he’d seen. As we fled, the soldiers killed ten children in the water. They killed a lot of adults, cut off their hands, put them in baskets, and took them to the white man, who counted two hundred hands. They killed my little sister, threw her in a house, and set it on fire. The report caused a sensation. The British Parliament forced Belgium to set up an independent commission of inquiry. Between October nineteen-oh-four and February nineteen-oh-five, Leopold’s own commission investigated.

They confirmed Casement’s findings in every detail. Officials were arrested. One Belgian national was given five years for causing the shooting of at least one hundred twenty-two Congolese natives. But Leopold himself was never charged. He was a king. The Congo was technically his private property. What could anyone do?

The First Human Rights Campaign

In nineteen-oh-four, E. D. Morel and Roger Casement founded the Congo Reform Association. It’s been described as the first large-scale human rights organization. Morel served as Honorary Secretary. They called each other by nicknames—Morel was Bulldog, Casement was Tiger. Their strategy was unprecedented. They would mobilize public opinion through newspapers, pamphlets, books, and political lobbying.

But most importantly, they would use photography. Remember Alice Harris and her photograph of Nsala staring at his daughter’s severed hand? Harris and her husband John had taken dozens of photographs documenting atrocities. Children with amputated hands. Mutilated adults. Hostages in stockades. The chicotte whip. The Congo Reform Association created what they called Congo Atrocity Lantern Lectures.

Sixty photographic slides presented in public halls. John Harris wrote that the photograph of Nsala was most telling. As a slide, he said, it will rouse any audience to an outburst of rage. The expression on the father’s face, the horror of the bystanders, the mute appeal of the hand and foot will speak to the most skeptical. In early nineteen-oh-six, John and Alice Harris toured the United States. They presented their images at two hundred meetings in forty-nine cities. The lantern lectures had something of the same public appeal as a modern rock tour. Thousands of people attended each lecture.

In December nineteen-oh-six, the New York American used Harris’s photographs to illustrate articles on Congo atrocities for an entire week. This was the first photographic campaign in support of human rights. The first time atrocity photographs were used to mobilize international opinion. Mark Twain joined the cause. In nineteen-oh-five, he published King Leopold’s Soliloquy—a satirical pamphlet where Leopold complains about being exposed. Twain has Leopold say: The kodak has been a sore calamity to us. The most powerful enemy that has confronted us, indeed. Arthur Conan Doyle—creator of Sherlock Holmes—wrote The Crime of the Congo in nineteen-oh-eight.

He completed it in eight days, fueled by burning indignation. There are many of us in England, he wrote, who consider the crime which has been wrought in the Congo lands by King Leopold of Belgium and his followers to be the greatest which has ever been known in human annals. The pressure mounted. The British House of Commons passed a resolution condemning the Congo Free State in May nineteen-oh-three. The U. S. Congress demanded an end to Leopold’s rule. Leopold fought back with propaganda, but he was losing.

The photographs were too powerful. The testimony too overwhelming. By nineteen-oh-eight, he had no choice.

Leopold’s Final Days

On August tenth, nineteen-oh-eight, the Belgian Parliament voted to annex the Congo Free State. Leopold didn’t go quietly. He negotiated terms. Belgium would pay one hundred ten million francs to cover outstanding debts. Forty-five point five million francs for his building projects in Belgium. And fifty million francs as a personal payment to Leopold himself. A payment. For surrendering a colony he’d extracted through mass murder.

On November fifteenth, nineteen-oh-eight, the official annexation ceremony took place at Boma. The Congo became Belgian Congo. The worst abuses were officially prohibited, though exploitation would continue for decades. Before the transfer, Leopold gave one final order. Burn the archives. All of them. For eight days, fires burned as the entire documentary record of the Congo Free State was systematically destroyed. Every order, every report, every piece of correspondence that might reveal the full scope of what had happened.

Leopold told his aide: They have no right to know what I did there. Leopold spent his final year with his mistress, Caroline Lacroix. He’d met her in Paris when he was sixty-five and she was sixteen—a prostitute. He lavished her with properties and the title Baroness de Vaughan. She became known as La reine du Congo—The Queen of the Congo. He once reportedly spent three million francs on dresses for her at a single store visit. With his Congo wealth, Leopold had built monuments across Belgium. The Arcade du Cinquantenaire in Brussels.

The Royal Palace facade. The Royal Museum for Central Africa at Tervuren. The Japanese Tower and Chinese Pavilion at Laeken. Six thousand seven hundred hectares of forests and châteaux in the Ardennes. All of it built with blood money. Leopold the Second died at Laeken Palace on December seventeenth, nineteen-oh-nine. He was seventy-four years old. He’d married Caroline Lacroix in a religious ceremony five days before his death, though the marriage was invalid under Belgian law.

His funeral cortege passed through Brussels. The crowd booed. Even his own people knew what he was. Historian Adam Hochschild later wrote: I would guess that he felt no guilt whatsoever about anything he had done in the Congo. I would guess that he was proud that he had raised Belgium’s status in the imperial world by means of this colony. And that, most of all, he was satisfied at how rich he had made himself.

Act 4

The Aftermath

E. D. Morel continued his advocacy work. During World War One, he became a leading pacifist and was imprisoned for six months in nineteen seventeen. In nineteen twenty-two, he was elected Labour Member of Parliament for Dundee, defeating Winston Churchill. He died of a heart attack in nineteen twenty-four. Roger Casement’s story ended more tragically. In nineteen-oh-five, he was made Companion of the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George for his Congo work.

He never opened the parcel containing the insignia. In nineteen eleven, he was knighted for his report on atrocities in the Peruvian Amazon—yes, it was happening there too. But Casement had become increasingly involved in Irish nationalism. He helped organize the Irish National Volunteers. In November nineteen fourteen, he traveled to Berlin seeking German support for Irish independence. In April nineteen sixteen, he sailed to Ireland in a German submarine for the Easter Rising. He was arrested on April twenty-fourth. Convicted of treason on June twenty-ninth.

And hanged at Pentonville Prison on August third, nineteen sixteen. In a letter written in the spring of nineteen-oh-seven, Casement reflected on what his time in the Congo had taught him. In those lonely Congo forests, he wrote, where I found Leopold, I found also myself, the incorrigible Irishman. Alice Harris lived to be one hundred years old. She continued working with the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines’ Protection Society. When her husband John was knighted in nineteen thirty-three, she famously said: Don’t call me Lady. In nineteen seventy, on her one hundredth birthday, she was interviewed by BBC Radio Four. She died November twenty-fourth, nineteen seventy.

Her photographs remain in the Harris Papers and Lantern Slide Collection, owned by Anti-Slavery International and managed by Autograph ABP in London. They’re still powerful. Still unbearable to look at. Still necessary.

The Rubber Connection

The Congo Free State collapsed not because of moral outcry alone, but because of economics. Congo rubber was nicknamed red rubber—red for the blood of the Africans killed during production. But it came from wild vines that were being harvested to extinction. The system was unsustainable. Meanwhile, in British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, something different was happening. Plantation rubber. In eighteen seventy-six—the same year Leopold hosted his Brussels conference—a British botanist named Henry Wickham smuggled seventy thousand rubber tree seeds out of Brazil. They were planted in Ceylon and Malaya.

By nineteen-oh-five, plantation rubber was becoming commercially viable. By nineteen ten, it was cheaper than wild rubber. By nineteen fourteen, plantation rubber accounted for fifty-nine percent of global production. By nineteen twenty-two, ninety-three percent. The Congo couldn’t compete. In eighteen ninety, Congo produced eight hundred fifty tons. By nineteen hundred, five thousand eight hundred tons. Peak was around nineteen-oh-four at sixty-five hundred tons.

By nineteen ten, production had fallen to forty-eight hundred tons. By nineteen twenty-two, just eight hundred tons. The horror of Leopold’s Congo didn’t end the rubber trade. It just shifted the rubber trade elsewhere. And those British plantation colonies would later attempt their own monopoly scheme. After World War One, rubber prices collapsed. British planters, now controlling about seventy-five percent of global production, sought price supports. In November nineteen twenty-two, Winston Churchill—then Secretary of State for the Colonies—enacted the Stevenson Plan.

It restricted rubber exports from British Malaya and Ceylon through a quota system designed to drive up prices. Rubber prices tripled. The United States, which consumed seventy-five percent of global rubber, was furious. American companies scrambled for alternatives. DuPont developed neoprene synthetic rubber. Goodyear developed plantations in the Philippines and Costa Rica. Firestone developed massive plantations in Liberia. And Henry Ford decided to break the British monopoly by building his own rubber empire in the Amazon.

That venture was called Fordlandia. It’s another story of colonial ambition, hubris, and failure. Another story of how global commodity economics drove disasters that killed thousands and ruined millions more. The same rubber boom that fueled Leopold’s atrocities from eighteen ninety to nineteen-oh-eight set the stage for the monopoly schemes of the nineteen twenties and Ford’s Amazon catastrophe. Red rubber gave way to plantation rubber gave way to monopoly rubber gave way to corporate rubber. But the pattern remained the same. Power, profit, and human cost.

What Remains

In the center of Kinshasa, there used to be a statue of Leopold the Second on horseback. It was torn down after Congolese independence in nineteen sixty. But Leopold’s buildings still stand in Brussels. The Arcade du Cinquantenaire. The Royal Museum for Central Africa. Tourists photograph them without knowing what paid for them. The museum at Tervuren still exists, though it was renovated and reopened in twenty eighteen with exhibitions acknowledging Belgium’s colonial crimes. But for decades, it displayed Congo artifacts with no mention of how they were obtained or at what cost.

In twenty twenty, during the Black Lives Matter protests, Leopold’s statues across Belgium were vandalized and removed. Some were decapitated. Others spray-painted with the words assassin and shame. King Philippe of Belgium wrote a letter to the President of the Democratic Republic of Congo expressing his deepest regrets for wounds of the past. He stopped short of an apology. The Congo Reform Association pioneered techniques that would be used by every human rights campaign that followed. Photography as evidence. Public lectures to build awareness.

International pressure campaigns. Celebrity endorsements. These tools are still used today by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and countless other organizations. The phrase crimes against humanity, first used by George Washington Williams in eighteen ninety, became part of international law. It was codified at the Nuremberg trials. It’s now a cornerstone of international criminal justice. But the most important legacy is simpler. We know their names.

Nsala of Wala. Boali, his five-year-old daughter. Bonginganoa, his wife. Mola Ekulite with his crushed hands. Yoka, the child who survived. Leopold tried to erase the evidence. He burned the archives. He died in his palace, wealthy and unrepentant.

But the photographs survived. The testimony survived. The names survived. Ten million people died in the Congo Free State between eighteen eighty-five and nineteen-oh-eight. Most of their names are lost. But what happened to them is not forgotten. And the man who did it—the humanitarian who brought civilization—will be remembered for what he truly was. A king who never saw his crime.

But couldn’t hide from it.